what is this page?

I, Olivia Guest have collected extracts of my writings on the Turing test, which Alan Turing referred to as the Imitation Game. For the reader, this page merely assumes you're interested in what I have to say on this topic. And so, below are a chronologically ordered series of extracts — in each case you may want to click through to the full paper for more context.

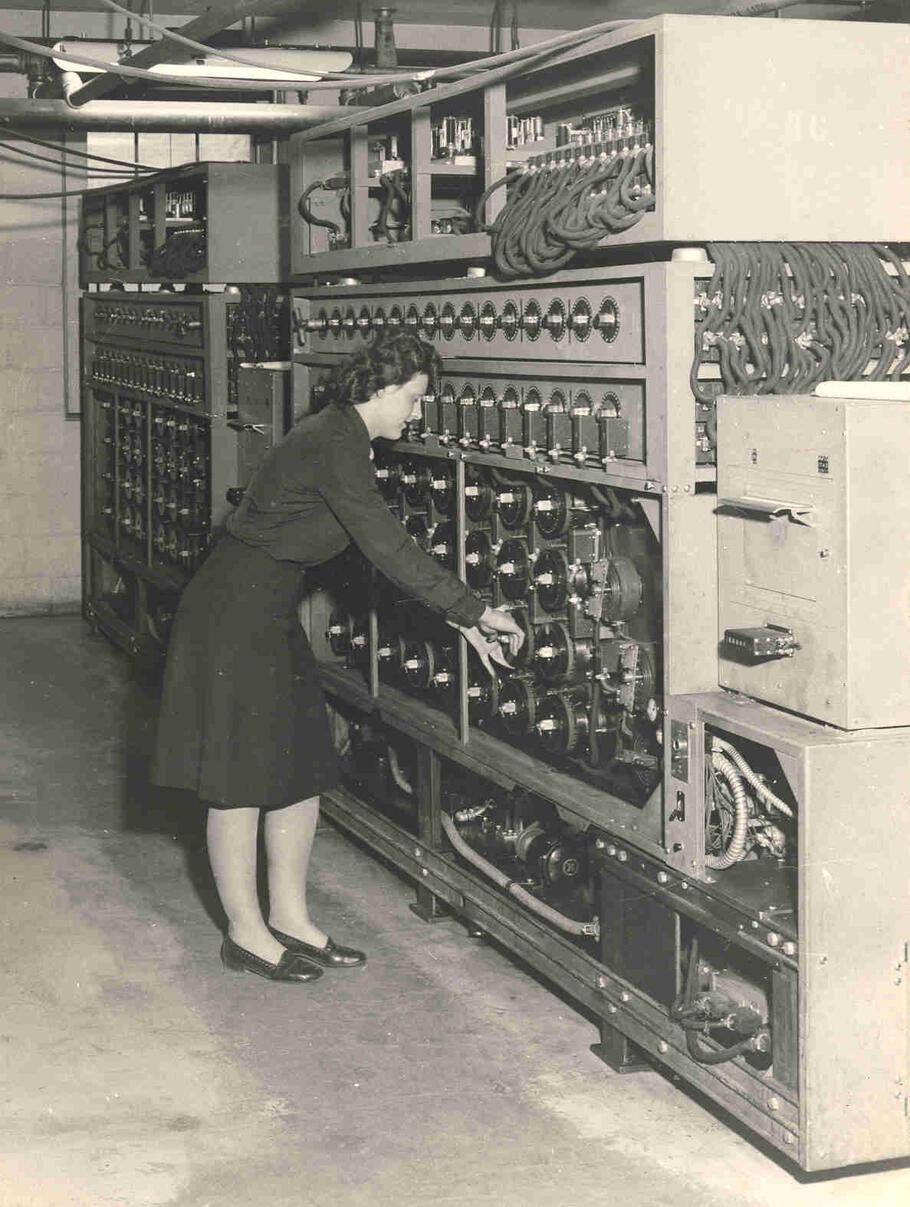

"NACA computer working with microscope and calculator, 1954." (Rare Historical Photos, 2025; also NASA, 2016)

what is the Turing test?

From Erscoi et al (2023, p. 11), we explain:

Turing introduces his original formulation of the test by means of “a game which we call the ‘imitation game’. It is played with three people, a man (A), a woman (B), and an interrogator (C) who may be of either sex. [...] The object of the game for the third player (B) is to help the interrogator. The best strategy for her is probably to give truthful answers. She can add such things as ‘I am the woman, don’t listen to him!’ to her answers, but it will avail nothing as the man can make similar remarks.” (pp. 433–434) Turing (1950) then asks “‘What will happen when a machine takes the part of A [the man] in this game?’ Will the interrogator decide wrongly as often when the game is played like this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman? These questions replace our original, ‘Can machines think?”’ (p. 434)

On page 12, we also underline that:

the original imitation game serves as a palimpsest or pentimento to modern conceptions of the Turing test, which remove gender and focus on whether a chatbot can trick a human into thinking it is another person (Kind 2022). What we mean is that any attempts to paint over or scrape away, i.e., whitewash, the origins of what is now called “the Turing test” by AI researchers ignore and obfuscate both the gendered history and the behaviourist assumptions of Turing (1950). In essence, the modern Turing test does not constitute a reimagining of the original game in any deep way, but a still flawed test, fraught with behaviourist assumptions, such as that personhood or intelligence can be inferred from looking at the inputs and outputs of a text-based chat (viz. Guest and Martin 2023). Authors that discuss the test both try hard to be traced back to Turing (1950) for providence and pres-tige, but also to avoid mentioning gender and any of the original arguments, especially about extrasensory perception.

Judith Genova in Turing’s sexual guessing game (1994, p. 315) explains:

Seeing himself as a mathematical Pygmalion, armed with recursion and a few other tricks, Turing hoped to create a machine that could create other machines, and thus begin a new kind of evolution.

Women codebreakers at Bletcheley Park during the Second World War.

Pygmalion Displacement: When Humanising AI Dehumanises Women

- Erscoi, L., Kleinherenbrink, A., & Guest, O. (2023). Pygmalion Displacement: When Humanising AI Dehumanises Women. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/jqxb6

Herein, we analyse the process through which women are dehumanised and AI is humanised, which we dub Pygmalion displacement. The section most relevant, in fact dedicated to the Turing test, is called Interlude: Can Women Think? — reading the whole of it might be useful to understand how the Turing test can be used to harm women. Specifically, we say on page 12:

Turing (1950) manages to seamlessly pit a woman both against a machine and against patriarchal standards of masculinity, wherein she must convince an interrogator of her humanity. Pygmalion displacement is evidently occurring here as her presence becomes fully erased almost instantly, where even player B is now, without any given reason, a man further down in the original text.

[...]

Turing’s thought experiment sets the stage for fictional replacements of women by machines to become the blueprint for historical, present, and future trends of Pygmalion displacement of human beings along gendered lines.

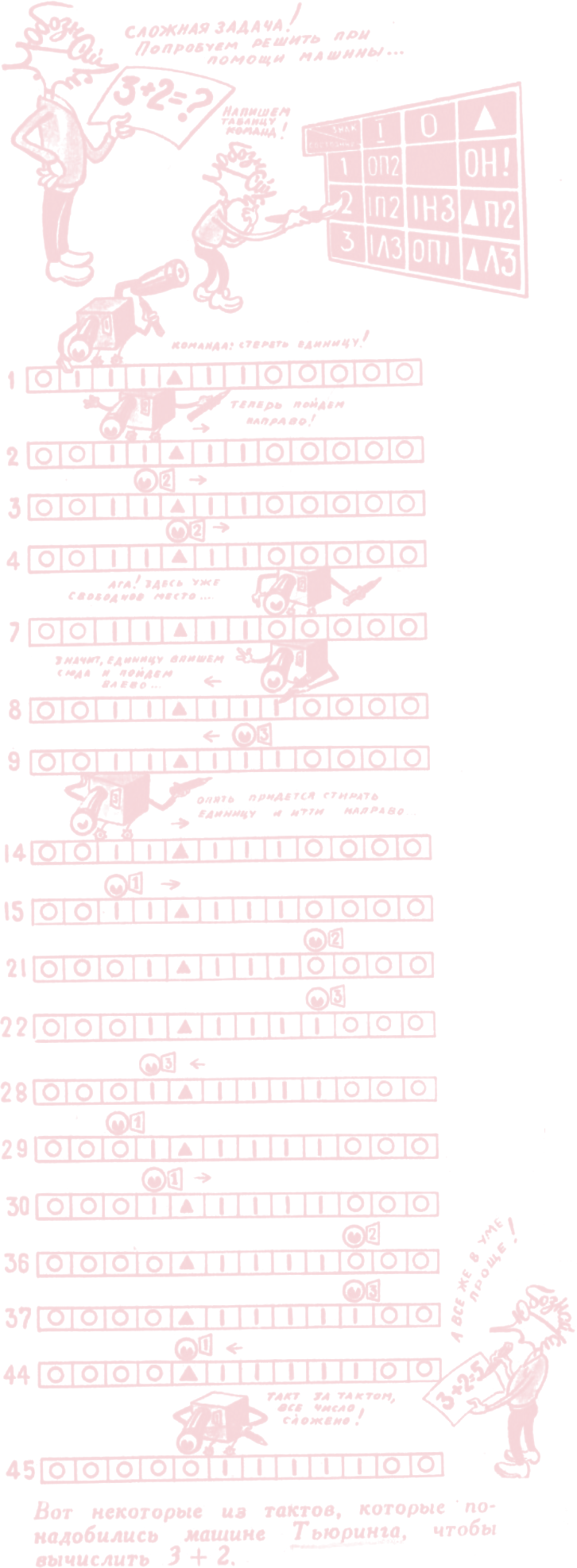

Figure 2 from Erscoi et al., 2023.

On Logical Inference over Brains, Behaviour, and Artificial Neural Networks

- Guest, O. & Martin, A. E. (2023). On Logical Inference over Brains, Behaviour, and Artificial Neural Networks. Computational Brain & Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42113-022-00166-x

Herein we talk about how scientists reason about artificial neural networks' apparent modelling successes. We elaborate on how we as scientists can be negatively influenced by the Turing test; Guest & Martin (2023, p. 215):

Based on the discovery of such correlations over correlations, CCN proposes a theoretical position about the contents of brain states, e.g., “our IT-geometry-supervised deep representation fully explains our IT data” (emphasis added; Khaligh-Razavi & Kriegeskorte, 2014, p. 24), or that using ANNs “explains brain activity deeper in the brain [and such models] provide a suitable computational basis for visual processing in the brain, allowing to decode feed-forward representations in the visual brain.” (emphasis added; Ramakrishnan et al., 2015, p. 371). Furthermore, some propose that “[t]o the computational neuroscientist, ANNs are theoretical vehicles that aid in the understanding of neural information processing” (emphasis added; van Gerven & Bohte, 2017, p. 1). This betrays very strong assumptions in CCN about the explanatory virtue of correlational results and how metatheoretical inferences are drawn. This specific belief system involving correlation could be seen as the result of importing the Turing test (Turing, 1950) from computer science and philosophy of mind to CCN, without bearing in mind that the Turing test is not per se useful for furthering a mechanistic understanding, but rather for elucidating functional roles. The Turing test, in its most abstract form, evaluates if an engineered system, like a chatbot, can converse in such a way as to pass as human, i.e., can an algorithm convince a human judge that it is indistinguishable from a human? If yes, then the machine is said to have passed the Turing test and on that — functional, correlational, but not mechanistic — basis be human-like. The insights from the engineering-oriented Turing test, can lead CCN astray if we do not methodically take into account the principle of multiple realizability (Fodor & Pylyshyn, 1988; Putnam, 1967; Quine, 1951): dramatically different substrates, implementations, mechanisms, can nonetheless perform the same input-output mappings (i.e., can correlate with each other without being otherwise “the same”).

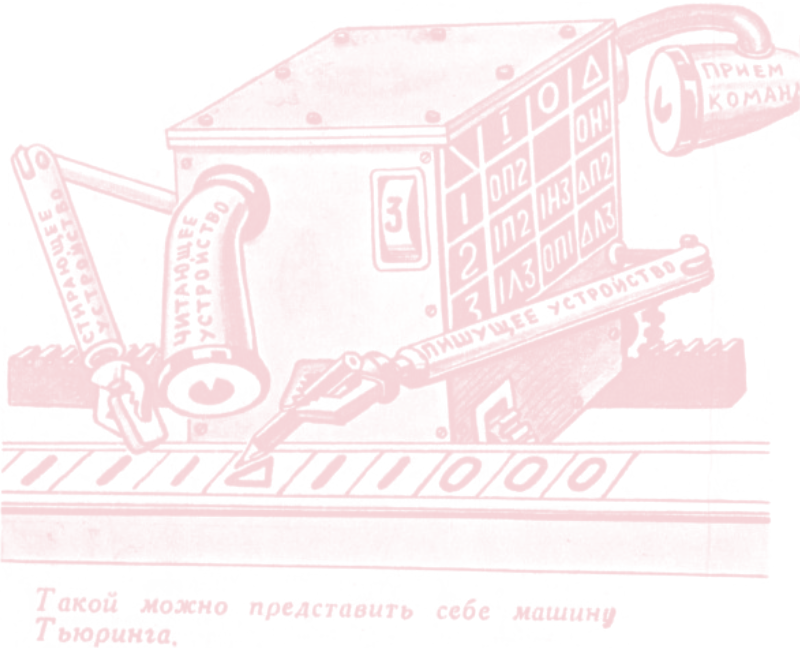

Figure from Tekhnika Molodezhi (Apr. 1955, p.9).

Further down in the same paper, we return to summarise how the Turing test can affect our reasoning; Guest & Martin (2023, p. 224):

Misapplication of such metatheoretical logic, as we have expounded on herein, contributes to overpromising and underdelivering, impeding the progress of CCN as much as it does the fields that touch on AI generally. We do not argue that ANNs do not make highly useful models within CCN and the neuro- and cognitive sciences more broadly. Although “machine learning provides us with ever-increasing levels of performance, accompanied by a parallel rise in opaqueness” (Barak, 2017, p. 5), we do not believe using machine learning this way is the only source of lack of transparency and of lack of “open theorizing” (Guest & Martin, 2021) within CCN. Interdisciplines, like cognitive science, strive to properly allow for the scientific exchange of ideas and methods within and between their constituent participating disciplines. We wish to facilitate dialogue on how to theorize usefully when importing ideas to CCN from other related fields. An example of a maladaptively imported idea is that of the Turing test (Turing, 1950), which involves understanding and contextualizing the principle of multiple realizability. The Turing test sets out to differentiate the human(-like machine) from an algorithm, essentially a chatbot. Through behavioral probing, e.g., asking questions in natural language, the person performing the test attempts to ascertain if the agent (machine or person) answering is responding meaningfully differently to a person. If the machine can “trick” us into thinking it is a human, it is said to have passed the Turing test. The Turing test is very useful if we want to engineer algorithms that can exchange details with people seamlessly. However, if we take this test and use it to infer more than perhaps Alan Turing intended, that the machine indeed is a person (our P → Q), we have slipped into affirming the consequent and false analogy.

As we have shown, it is not unusual if formally treated to discern or derive fallacies in the CCN literature such as cum hoc ergo propter hoc (i.e., with the fact, therefore because of the fact, or “correlation does not imply causation”), begging the question, confirmation bias, false analogy — the root of these informal fallacies is the formal fallacy of affirming the consequent. The Turing test and similar functional role-based analogies allow us to stumble into a formal fallacy if we stray far from engineering systems and towards understanding human cognition. Ultimately, the lack of attention to the high potential for (mis)application of formal logic in CCN betrays its current theoretical underdevelopment. This is the case regardless of what the reasons are for this lack of (meta)theoretical aptitude. If we accept that a “theory is a scientific proposition [...] that introduces causal relations with the aim of describing, explaining, and/or predicting a set of phenomena” (Guest & Martin, 2021, p. 794), then the field-level theory that much of CCN work is based on has logical inconsistencies, namely manifesting as the formal fallacy of affirming the consequent. The ability to critically evaluate this was granted to us in part by the metatheoretical calculus, the formal model of the discourse, we built herein.

What Makes a Good Theory, and How Do We Make a Theory Good?

- Guest, O. (2024). What Makes a Good Theory, and How Do We Make a Theory Good?. Computational Brain & Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42113-023-00193-2

In this paper I touch on the antecendent and interconnected theoretical frameworks that underlie contemporary AI approaches, including artificial neural networks; Guest (2024, p. 518):

A behaviourist framework is genealogically linked to, for example, reinforcement learning and a specific take on the field of (comparative) psychology, inter alia. It is also related to the perspective on human (and other) cognitions granted by the Turing test (cf. Guest and Martin, 2023; Erscoi et al., 2023). In many ways, a metatheoretical calculus for reinforcement learning as used in AI (e.g. Sutton et al., 1998), if it took into account genealogy, would have to relate all these elements, such as answering when, how, and why behaviourism is seen as unethical (e.g. applied to treatment or education, Kirkham, 2017; Kumar and Kumar, 2019), seen as not a useful framing of what is attempted to be scientifically understood (Guest & Martin, 2023), or seen as both (Erscoi et al., 2023). These parts of analysing a modern AI reinforcement learning paradigm only drop into place when seen through a genealogical lens.

"The German army and navy widely used Enigma machines to encrypt radio messages to troops in the field or U-boats at sea. Decrypting the transmissions sent using the Kriegsmarine’s four-rotor version proved especially difficult and time consuming for the Allies, but the U.S. Navy’s high-speed bombe (shown here) greatly facilitated the process." (Sears, 2016)