We have certainly been here before. Many many times in the past, companies — just like artificial intelligence (AI) companies now — have lied to us to sell us products. Not only is there no reason to assume the AI industry is different, there is in fact much to make us think they are knowingly misleading us. To understand this, take a look at this great work called Late lessons from early warnings: science, precaution, innovation by the European Environment Agency (EEA):

The 2013 Late lessons from early warnings report is the second of its type produced by the European Environment Agency (EEA) in collaboration with a broad range of external authors and peer reviewers. The case studies across both volumes of Late lessons from early warnings cover a diverse range of chemical and technological innovations, and highlight a number of systemic problems. The 'Late Lessons Project' illustrates how damaging and costly the misuse or neglect of the precautionary principle can be, using case studies and a synthesis of the lessons to be learned and applied to maximising innovations whilst minimising harms.

Also there are well-known patterns of our thinking that are affected by interacting with certain machines. As Brian P. Bloomfield (1987, p. 72) explains four decades ago:

While opacity is a distinguishing feature of many other areas of science and technology, the myths surrounding computing may stem less from the fact that it is an opaque esoteric subject and more from the way in which it can be seen to blur the boundary between people and machines (Turkle 1984). To be sure, most people do not understand the workings of a television set or how to program their video cassette recorders properly, but then they do not usually believe that these machines can have intelligence. The public myths about computing and AI are also no doubt due to the ways in which computers are often depicted in the mass media — e.g. as an abstract source of wisdom, or as a mechanical brain.

For detailed analysis and more examples see:

- Guest, O., Suarez, M., Müller, B., et al. (2025). Against the Uncritical Adoption of 'AI' Technologies in Academia. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17065099

Another related aspect — described by Valentina Ponomareva (1998) — is that:

it is impossible to create an absolutely reliable automatic system, and sooner or later people face the necessity to act after equipment fails. [...] If the cosmonaut loses such skills because of [their] passive role [due to being typically limited to monitoring and observation only], the probability of [their] choosing and carrying out the right procedure in an emergency would be small. This contradiction is inherent in automatic control systems.For more on this angle of AI see:

- Guest, O. (2025). What Does 'Human-Centred AI' Mean?. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2507.19960

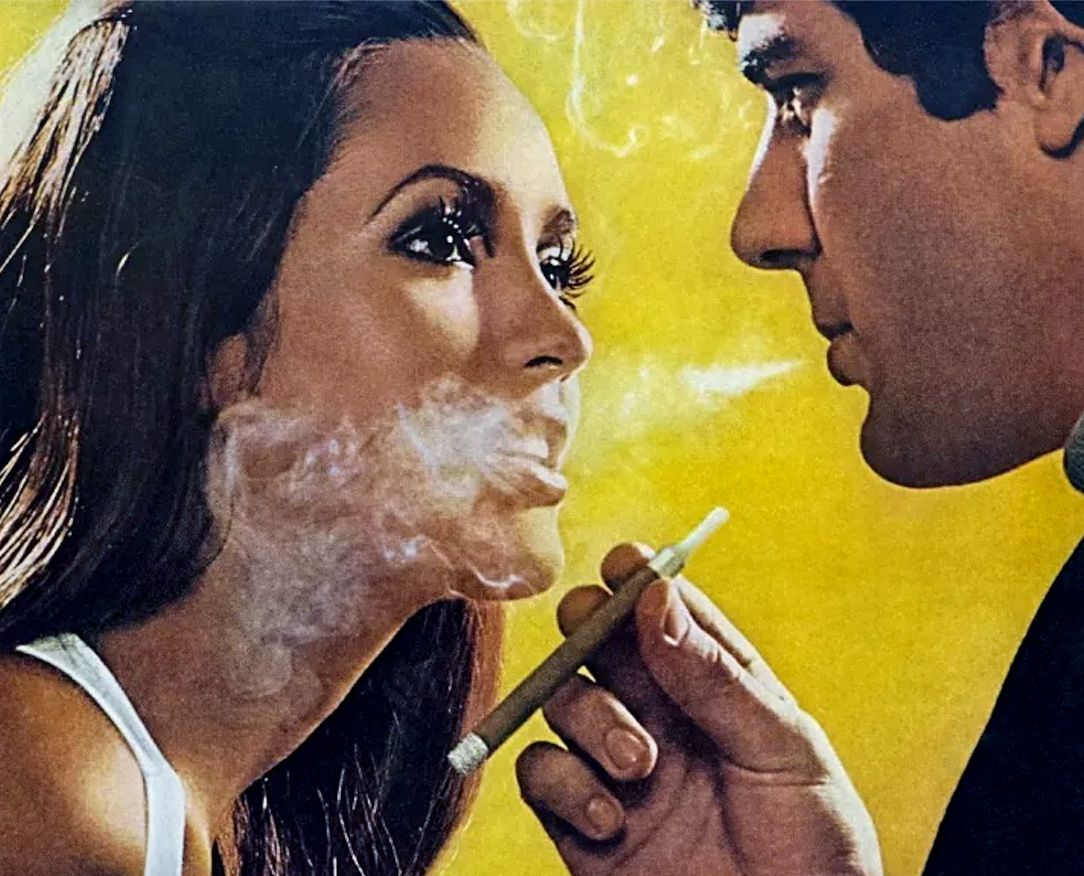

Our present predicament is enabled by the fact that regulation is apparently not only missing in the case of AI, but also very hard to enforce even for industries where there is complete mainstream acceptance of their malevolent goals and harmful practices. The tobacco industry for example, still publishes research even in journals which try to enforce complete bans on such work. For one, they run disinformation campaigns, as Annamaria Baba and colleagues (2011) explain:

Internal tobacco industry documents that have been made available through litigation give us the opportunity to analyze one industry’s involvement in a broader industry strategy to secure enactment of the data access and data quality provisions. These documents provide unprecedented insight into the industry’s motives, strategies, and tactics to challenge the scientific basis for public health policies. In the 1990s Philip Morris implemented a 10-year “sound science” public relations campaign to create controversy regarding evidence that environmental toxins cause disease. Our article describes the tobacco industry’s later campaign to advance the “sound science” concept via legislation.

For another, as mentioned the tobacco industry continues to indirectly or directly publish medical research, as Irene van den Berg and coauthors (2024) document:

In recent years the “big four” global tobacco companies (according to sales)—Philip Morris International (PMI)/Altria, British American Tobacco (BAT), Imperial Brands, and Japan Tobacco International (JTI)—have invested billions in companies that produce medicines or other medical products. These investments include treatments for conditions caused or aggravated by smoking. For example, Vectura, a subsidiary of PMI since 2021, produces an inhaler used by patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. And JTI’s pharmaceutical branch produces treatments for lung cancer, skin conditions such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, and heart disease.

The same tactics are also used by the petrochemical industry to sabotage science and regulation. If you want to read more on that read Linda Knoester and colleagues (2025): Academic Collaborations and Public Health: Lessons from Dutch Universities' Tobacco Industry Partnerships for Fossil Fuel Ties.

The AI and generally the technology industry is no different. Why should they be? They fund researchers and institutes, therefore creating academics and publications with conflicting interests, which often go un- or under-acknowledged especially in mainstream coverage. These conflicts of interest are sometimes very time consuming to dig up, for example see: Nature's Folly: A Response to Nature's "Loneliness and suicide mitigation for students using GPT3-enabled chatbots".

Standing against these corrosive forces is important, especially since they converge. For example, the AI industry wastefully burns fossil fuels while pretending to want to combat climate crisis. Read more here:

- Suarez, M., Müller, B.,Guest, O., & van Rooij, I. (2025). Critical AI Literacy: Beyond hegemonic perspectives on sustainability. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15677839

- Guest, O., Suarez, M., Müller, B., et al. (2025). Against the Uncritical Adoption of 'AI' Technologies in Academia. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17065099

If you want to help yourself and others notice these harmful frames, even just perusing websites and papers such as these on critical artificial intelligence literacy is more than enough for a first step. If you're interested in actively disentangling, you can consider thinking deeply about what we outline here:

- Guest, O., Suarez, M., & van Rooij, I. (2025). Towards Critical Artificial Intelligence Literacies. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17786243

These, shown in Figure 1 above (Guest et al., 2025), are ways of approaching the core problems AI causes and is caused by. Conceptual Clarity, which we say is the requirement for academic terms to have clear meanings and/or for users and proponents of such terms to accept where confusions still exist:

AI-adjacent and -affected fields experience severe terminological crises, wherein terms fail to refer and change meaning as a function of the speakers’ and audiences’ whims (Alkhatib 2024; Bender et al. 2025; Guest 2025; Guest, Suarez, et al. 2025; Schwerzmann 2025; van Rooij, Guest, et al. 2024). To sidestep this we suggest thinking about what words mean in the context of describing, defining, and discussing AI.

Critical Thinking, which in this context we think is:

as Isabelle Stengers (2018) explains, “the ability to be vigilant about one’s abstractions, to not be blindly led by them.” (p. 111) For ‘AI’ in the classroom this can be exercised with two steps (Guest 2025). First, students can ask themselves if their cognitive labour is being affected by an artifact; and if ‘yes’ then they can ask what that relationship means for their specific context. If they pick chatbots, it becomes obvious that these so-called tools damage their ability to learn, while also harming other people and planet (Guest, Suarez, et al. 2025; Suarez et al. 2025).

"Decoloniality is the decentring of views which stem from white and masculine supremacy, technosolutionism, and fascism" (Guest et al, 2025, p. 5):

decolonial strategies can range from pushing back against the onslaught of AI logics in our academic environments to (re)centring, uplifting, and protecting of non-mainstream perspectives from those outside the privileged classes with a goal of reducing harm, increasing justice, and cultivating empathy in our colleagues and students. AI is inimical to running on anything but colonial lines. Within computational and other fields affected by AI, any academic who works towards “challenging the status quo faces systemic rejection, resistance, and exclusion.” (Birhane and Guest 2021, p. 61) Tracing these trends of how these fields treat their thinkers, and how their mainstream views affect society, illuminates historical precedents for gendered, racialised, and other harms (Benjamin 2019; Erscoi et al. 2023; Gebru et al. 2024; Hicks 2017; Saini 2019).

Respecting Expertise, which actively involves stopping people from falsely claiming to be AI experts, as we explain (p. 6):

Academic expertise can only continue to exist if statements made by academics are understood as coming from highly skilled research and educational practitioners. [...] AI upends all this, violating the compact between academia and society and within academia under its expansionist imperialist scheme (Guest, Suarez, et al. 2025; Solomonides et al. 1985). Sherry Turkle (1984) describes AI as a “colonising discipline” that sweeps away everything that came before under the guise of “intellectual immaturity” — using social privilege to undermine expertise and breaking down the boundaries between disciplinary expertise. At the extreme, it becomes both the case that everybody is an expert in AI, provided they are white and male, and that nobody is an expert in anything since only experts in AI can now practice any form of academic pursuit. The same for education: nobody can teach without the imposition of AI into their learning environments.

Slow Science, developed by Isabelle Stengers into a radical perspective on science, is "a disposition towards preferring psychologically, techno-socially, and epistemically healthy practices." (Guest et al, 2025, p. 2) On page 7, we explain that

AI not only epitomises fast science, but turbocharges it, nosediving us into anti-science and anti-intellectualism. We see this pattern of condensing time in most computational fields (Guest 2025). “The ultra rapid computing machine” (Wiener 1948, 1950) serves two discursive purposes, as Sheryl Hamilton (1998) explains: “First, it forms an overall temporal backdrop against which various cybernetic dramas are played out. Second, condensed time becomes a measure of the performance of humans and machines.” (p. 193)

Anybody and in their own context and manner can use these skills to deal with the AI industry's attack on our public institutions and private lives.

Zooming out, there is much you can do and think about — even just refusing to accept industry frames and rejecting their products is non-negligible. If you want to read more, my relevant work can be found on the CAIL page.

Most importantly of all, resistance can and should take on many forms. Remember to rest and take care of yourself and your community. If talking to friends and colleagues is easy, then try to engage them on these issues. If it is not possible to do so, you can instead (or in addition) seek out allies online.